Research Interests

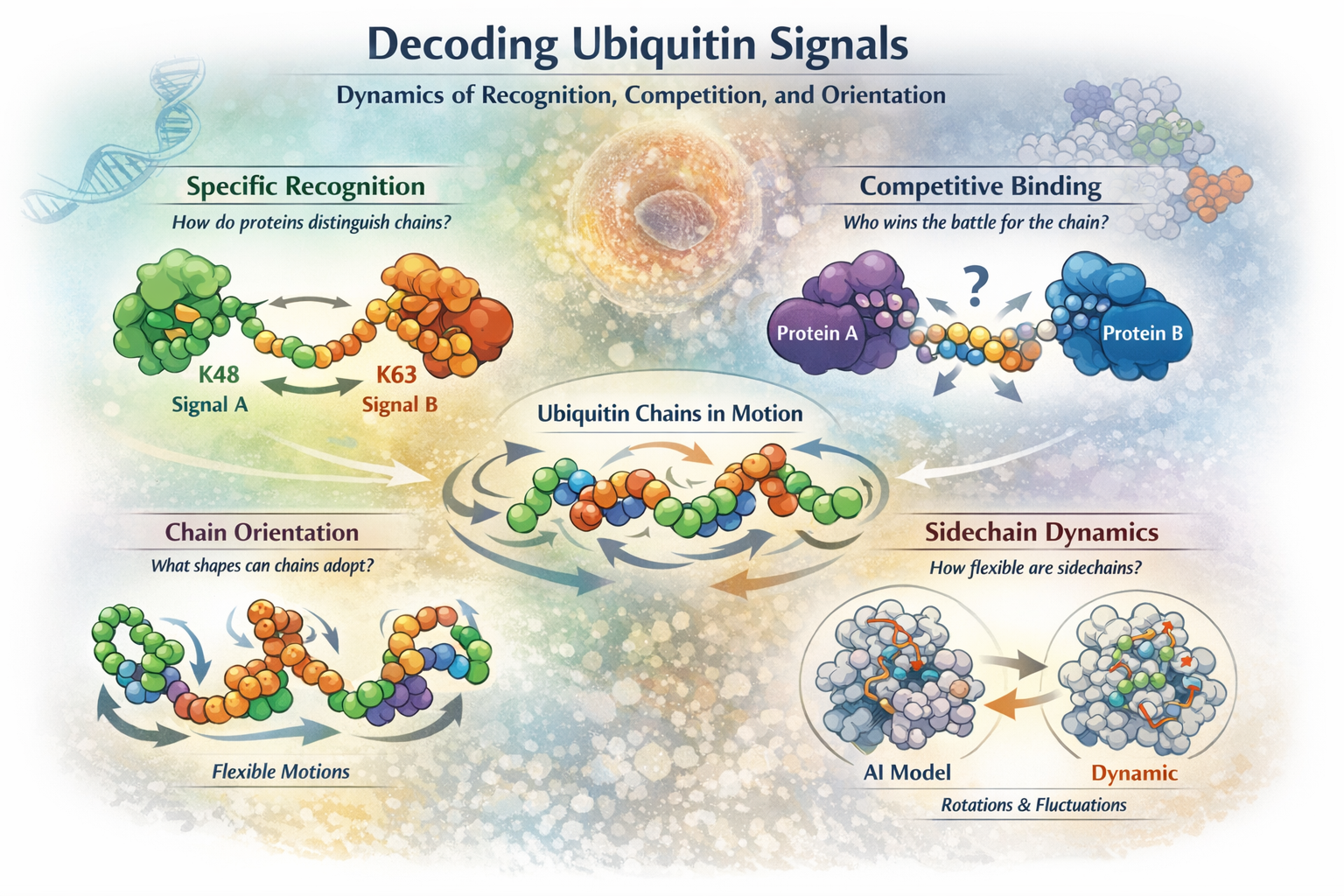

How proteins read, compete over, and dynamically interpret ubiquitin signals

Cells use ubiquitin chains as a rich molecular language. A single 76–amino-acid protein can be linked in multiple ways, forming chains that differ in length, topology, flexibility, and meaning. Remarkably, cells do not just attach ubiquitin—they read it. Our lab is fascinated by how this reading actually works at the level of molecular dynamics.

Rather than treating ubiquitin chains as static structures, we study them as dynamic, fluctuating objects whose motions, orientations, and competitions determine biological outcomes. In particular, we focus on the following questions:

How do proteins specifically recognize polyubiquitin chains?

Ubiquitin chains with different linkage types encode distinct cellular signals, yet many appear deceptively similar in static crystal structures. How do proteins reliably tell them apart in the crowded, noisy environment of the cell?

We investigate how conformational dynamics, transient states, and time-dependent recognition enable proteins to distinguish one ubiquitin chain from another. Static structures give us snapshots—but the real story unfolds in motion.

What happens when proteins compete for the same ubiquitin chain?

Inside cells, ubiquitin chains are rarely bound by just one partner. Multiple proteins may recognize, interpret, or remodel the same chain—sometimes cooperatively, sometimes competitively.

We ask how this competition plays out dynamically: Do proteins prefer different conformations of the same chain? Can binding by one factor reshape the chain and bias the next interaction?

What orientations can polyubiquitin chains actually adopt?

Polyubiquitin chains are flexible—but not infinitely so. Their motion is constrained by sterics, linkage chemistry, and intramolecular contacts.

We explore the orientational landscape of ubiquitin chains: which conformations are allowed, which are sterically forbidden, and which rare states may be functionally decisive despite being only fleetingly populated.

Are protein sidechains really “solved”?

AlphaFold has convincingly solved the problem of main-chain folding. But proteins are not just backbones.

We ask what remains unknown about sidechain dynamics—the local rearrangements that make contacts, transmit signals, and enable function. Has Levinthal’s paradox truly been resolved, or only for part of the problem?

If you are excited by molecular motion, hidden states, and proteins that refuse to sit still, you’ll feel right at home in YuraYura.

Konnichi-wa, fellow admirers of protein dynamics!

Yuragi is the Japanese word for dynamics. And because the main interest of my unit is to study protein dynamics and their physiological importance, YuraYura became the title of this site. Here, I plan to share recent research news and other material that might be helpful to students and fellow researchers.

So what actually are biomolecular dynamics?

There are many great reviews to answer this question, but let me advertise this one: Lewis Kay and Reid Alderson have recently written a nice review in Cell which summarizes our scientific field (what do we mean by biomolecular dynamics?) very nicely. Please check Fig. 6 of their review for a great visual impact. To avoid stealing their pretty figure, I will just verbally state the main points here:

Examples of biomolecular dynamics

1. Ligand binding (ligands can be both small molecules or macromolecules)

2. Allosteric interactions

3. Determination of molecular structures (proteins, DNA, RNA, etc.)

4. Folding

5. Detection of low-population "minor" (= almost "invisible" states)

6. Mechanisms (e.g. enzymatic reactions, amyloid fibril formation, ...)

7. Dynamic motions (domain motions, local motions, smaller fluctuations, ...; e.g.

flip-out of bases of DNA etc.)

8. Biochemistry of unstructured regions: domain linkers and intrinsically disordered

proteins

9. Weak, transient, non-specific interactions

Also these two points are emphasized. I agree that these 2 points make our field of protein dynamics

especially meaningful and thus fulfilling as researchers:

1. Molecular sample conditions: near physiological in vitro

conditions can be chosen (e.g. pH 7.4, intracellular ionic strength, reducing

conditions, temperature or even measurements in living cells)

2. We can monitor molecular processes in real time while they take

place (over seconds, minutes, hours, days).

News

November 14, 2025

Congratulations Daichi and Soki on your great paper in Analytical Chemistry. Nice combination of experiments (NMR, fluorescence), fluid mechanical MD-simulations, and comparative analysis of already known amyloid fibril structures!

November 12, 2025

Congratulations Anna and Ryo on your great paper "A minimal slow dialysis method for refolding inclusion body proteins: Structural application to NEDD8 and its Q40E mutant". Even though Anna worked in our lab for less than a year, this technical note is truly impressive and will be extremely helpful for researchers struggling to obtain pure protein from E. coli thanks to her refolding protocol.

August 24, 2024

ICMRBS 2024 was held at Seoul, South Korea. Thanks everyone for the fun! Great discussions in a great country. I am looking foward to visiting again some day. For now, I have to sort out all the great ideas I received there. Thanks to the great feedback, I am highly motivated to finish the current paper.

August 14, 2024

Moving away from our old Microsoft Sway site and back to a normal HTML website. Rebuilding this

slowly over time. Stay tuned!

May 15, 2024

Congratulations Takeda-san, Iwai-sensei, and everyone involved on an exciting paper on an enigmatic attenuation-of-function mutation (R306Q) in human OTULIN! Structurally speaking, it is quite understandable how R306 would partially attenuate OTULIN function. However, only considering the ternary molecular structure of the whole LUBAC complex bound to two monomers of OTULIN enzyme, we can understand how OTULIN R306Q can exert a dominant-negative effect on the function of LUBAC.

September 4, 2023

Congratulations Tomoki on your nice paper comparing cyclic and conventional K48-linked diubiquitin molecules in various aspects from structural dynamics to function and biophysical behavior.

August 18, 2023

I am happy to share that our paper on conformational dynamics of the HOIL-1L NZF domain has been accepted by the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

August 15, 2023

Our recent study on how proteins "feel" electric fields in their environment is now available online. Great job also on the pretty cover illustration!

Research Interests

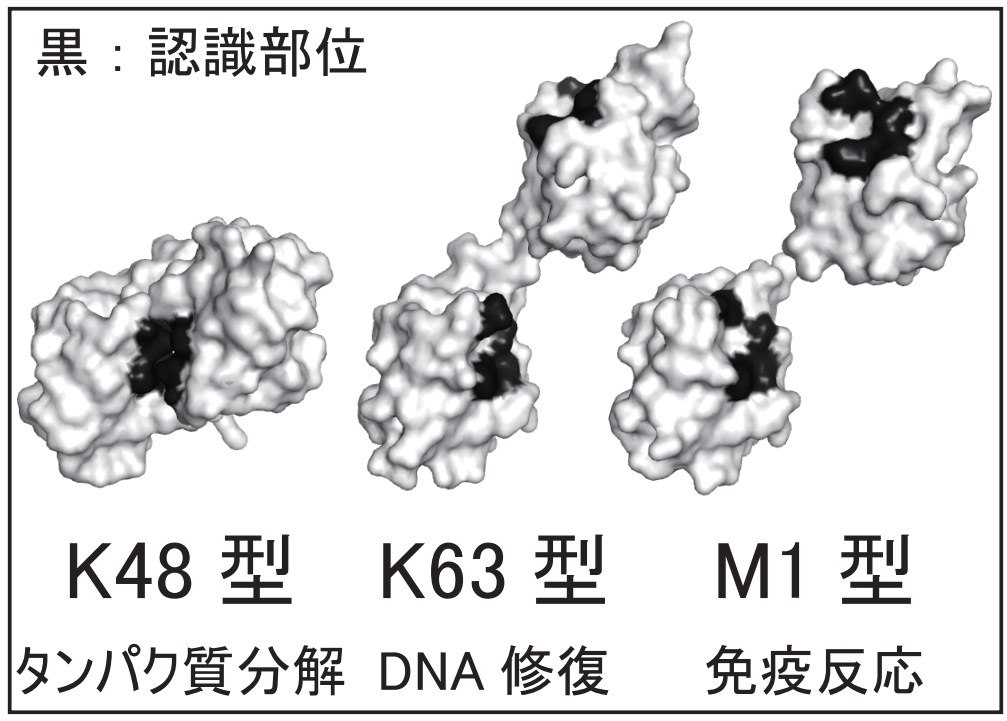

Research interest #1: Dynamic ubiquitin

Ubiquitin is a small protein, only 76 amino acids long. But it can be linked to another ubiquitin at 8 different points and these ubiquitin "chains" can become quite long and complex. Interestingly, inside cells different types of chains often have different meaning and are interpreted differently by the cellular machinery.

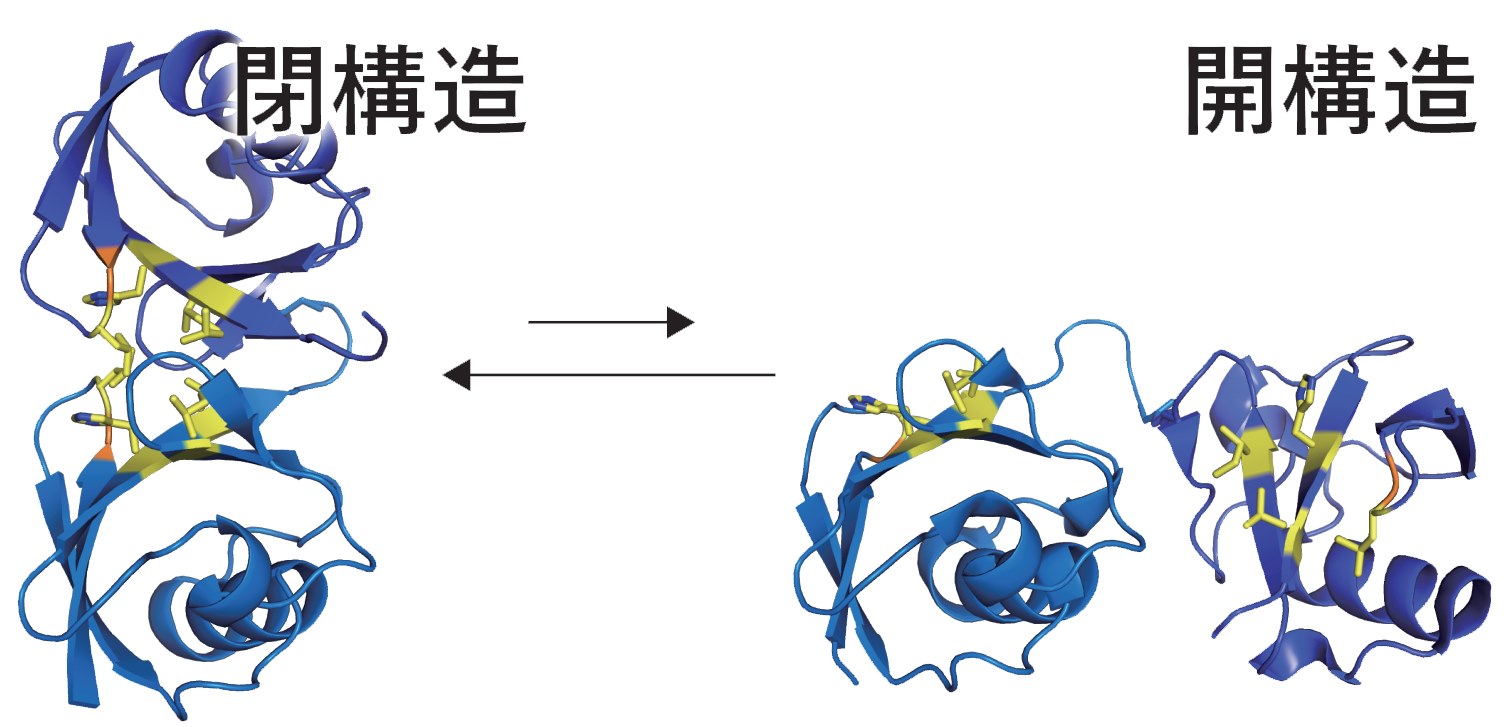

For example, a ubiquitin chain linked at residue lysine 48 (("K48-chain") to the C- terminus of the next ubiquitin) signals the cell that the protein connected to this ubiquitin chain should be degraded by the proteasome. Other ubiquitin chains also have different (non- proteolytic) functions. The K48 chain's simplest form: a K48-linked ubiquitin dimer is the most thoroughly studied example. Interestingly, even this simple dimer has intriguing dynamics such as a transition from a closed to an open conformation on solution. Interacting proteins that read out the ubiquitin-encoded signal bind the open form, not the closed one.

Selected publications

Dual Function of Phosphoubiquitin in E3 Activation of Parkin.

Walinda, E., Morimoto, D., Sugase, K., and Shirakawa, M.

J Biol Chem, 2016, 291, 16879-16891

See the full paper

Structural Dynamic Heterogeneity of Polyubiquitin Subunits Affects Phosphorylation

Susceptibility

Morimoto, D. & Walinda, E., Takashima, S., Nishizawa, M., Iwai, K., Shirakawa, M., and Sugase,

K.

Biochemistry, 2021, 60(8), 573-583

See the full paper

Solution structure of the HOIL-1L NZF domain reveals a conformational switch regulating

linear ubiquitin affinity

Walinda, E., Sugase, K., Ishii N., Shirakawa M., Iwai, K., Morimoto, D.

J Biol Chem, 2023, 299(9), 105165

See the full paper

Location of our unit inside of Kyoto University

You can find us at E-building, Room 204 on the Campus of the Faculty of Medicine.

If you want to stop by to chat, be sure to call us to make sure, someone is there (and not in other labs etc. at that time)!

Erik Walinda

606-8501 京都府 京都市左京区吉田近衛町 京都大学大学院 E棟109号室

Kyoto University, Faculty of Medicine E-109, Yoshida Konoecho, Sakyoku, Kyoto, 606-8501, Japan

Telephone: +81-(0)75-753-9299

E-mail: walinda.erik.6e [at] kyoto-u.ac.jp

I also have LINE, Kakao, and WeChat.

International Access

Kansai Airport

Alternatives: Tokyo-Haneda or Nagoya Airport

Kyoto Station

75 Minutes from Kansai Airport using the Express train "Haruka". Haneda airport is also nearer than one might think using the Shinkansen from Shinagawa and the Keikyu line from Haneda to Shinagawa.

Subway Station Jingu-Marutamachi

Collaborating labs and other useful websites

Check out the pretty pictures of ubiquitin chains and the recognizing proteins at Dr. Iwai's homepage. Also, Daichi @ Shirakawa-lab does an excellent job at providing updates on our collaborative research progress.

Shirakawa Laboratory at Kyoto University, Katsura Campus Iwai Laboratory at Kyoto University, Medical Campus Sakata Laboratory at Goettingen University, Faculty of Medicine Kenji's lab at Kyoto University, Faculty of Agriculture Erik Walinda, Publication list on Google Scholar

Links:

All ILAS Biochemistry Seminar Videos in order (under construction)

All ILAS Biotechnology Lecture Videos in order (under construction)